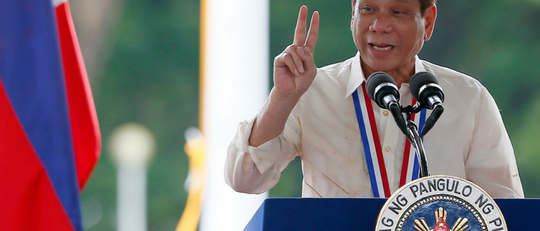

Rodrigo Duterte has only been in office eight weeks, but his presidency has already been a bloody one for the Philippines.

Elected in May, the 71-year-old Duterte coasted to victory on his tough-on-crime record and his inflammatory rhetoric, as well as his pledge to rid the country of drug dealers and criminals. It’s a promise he’s been keeping — with deadly repercussions.

More than 1,900 people have been killed since Duterte took office. Many of those executions have been carried out via the Philippine National Police (PNP), who have aggressively worked to locate and punish all individuals linked to the movement of drugs under the president’s new anti-crime agenda. But vigilantes, empowered by Duterte’s rhetoric and call for citizen action, have also taken matters into their own hands, with staggering results. While the PNP have been responsible for approximately 712 deaths, individual citizens have been linked to 1,067.

Like its neighboring countries, the Philippines have struggled with the drug trade and the violence it brings for many years. Particularly prevalent is crystal methamphetamine, better known in the Philippines as “shabu.” The drug is easily made and cheap, something that heightens its appeal for low-wage laborers and other struggling citizens. A 2012 U.N. report found that the Philippines had the highest rate of shabu usage of any country in the region, and also served as a central source of drugs for neighboring nations. Even within the country, some cities have been hit harder than others. According to the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency, more than 92 percent of districts in Manila are impacted by drug use — the highest in the country.

Faced with a crippling drug epidemic and no end in sight, it is unsurprising that many citizens found a hero in Duterte, who promised quick results and brought with him a record of no-nonsense anti-crime vigilance.

Duterte previously served as mayor of Davao City, an urban hub on the southern island of Mindanao, and took a hard stance on the city’s struggle with drugs. Davao “death squads” popped up under his leadership,ultimately killing more than a thousand people during his time in office. Believed to have been backed and encouraged by Duterte, they targeted individuals perceived as having any ties to crime and drugs. While accumulating a disconcerting body count, these vigilantes did help to curtail drug-related crime in Davao, something that Duterte emphasized during his presidential campaign.

Eliminating the drug trade was at the center of Duterte’s candidacy. “We will not stop until the last drug lord… and the last pusher have surrendered or are put either behind bars or below the ground, if they so wish,” Duterteproclaimed in his inaugural address to the country.

But Duterte’s approach is drastic. In addition to encouraging police to crack down hard on suspected drug dealers, the president has also called upon private citizens to do the same. “Please feel free to call us, the police, or do it yourself if you have the gun — you have my support,” he told viewers in a televised speech shortly after his election. “Shoot…[dealers] and I’ll give you a medal.”

While the image of a dealer may conjure up a figure with power, the majority of those who wind up being targeted are the same low-income workers who fall prey to drug consumption in the first place. Often hunted down at night and killed in urban areas, like the sprawling metropolis offered by Manila, their bodies are left for passers-by to discover the following day — bodies that are piling up with greater regularity.

For one thing, the figures notably do not include any deaths recorded between Duterte’s election and his inauguration. For another, it is difficult to determine just how many of the deaths directly correlate to the drug war — something that makes the high death toll all the more ominous.The most recent numbers about the nearly 2,000 people who have been killed were given at a press conference held on August 22, where PNP Chief Ronald dela Rosa briefed the Philippine Senate on the progress of the anti-drug agenda to date. Still, there are a few caveats regarding the current statistics.

Five-year-old Danica May Garcia is an especially tragic example of the Filipino people affected by Duterte’s policies. Garcia was killed by two vigilantes looking for her grandfather, who had reportedly surrendered to police earlier after learning he was suspected of dealing drugs. Caught in the crossfire, the younger Garcia was shot by the intruders, to the devastation of her family.

Stories like Danica Garcia’s are becoming more and more common under Duterte, but they are doing little to dim his popularity. The president enjoys enormous support from Filipinos, who appreciate his blunt manner and aggressive outlook on problems that have long troubled the country. Shabu is blamed for much of the poverty and violence that hangs over the Philippines, and residents are excited by the prospect of a leader willing to tackle the problem aggressively. They also enjoy Duterte’s colorful character, something that hasn’t gone over well abroad. The president is a hotrod, known for inflammatory and controversial statements as much as for his policies. He famously dismissed his daughter as a “drama queen” when she spoke out about her sexual assault, and once threatened to kill a smuggler, saying he would gladly go to prison if it meant being allowed to murder a criminal.

Popularity abroad doesn’t seem to be very high on Duterte’s priority list. The same anti-crime rhetoric that has made him so adored in the Philippines has done little to endear him elsewhere.

The United States, though working to preserve ties with the Philippines as it eyes China’s movements in the South China Sea, has expressed concern over Duterte’s attitude toward human rights. The U.N. has also issued a sharp rebuke to Manila, calling for an end to extrajudicial killings and abuses. Duterte’s response? A widely-covered news conference during which the inflammatory leader suggested that the Philippines might leave the U.N., while emphasizing his lack of regard for the international community’s censure.

Presidential terms in the Philippines are six years long, which means that Duterte will have a significant amount of time to carry out his aggressive agenda. At a news conference held last week, Duterte made clear that he intends to take advantage of this timeline. “This fight against drugs will continue to the last day of my term,” he assured voters.

;

;